Sam Angus has been a lawyer in Silicon Valley since the 1990s. Today, he represents some of the biggest names in the startup world, from the...

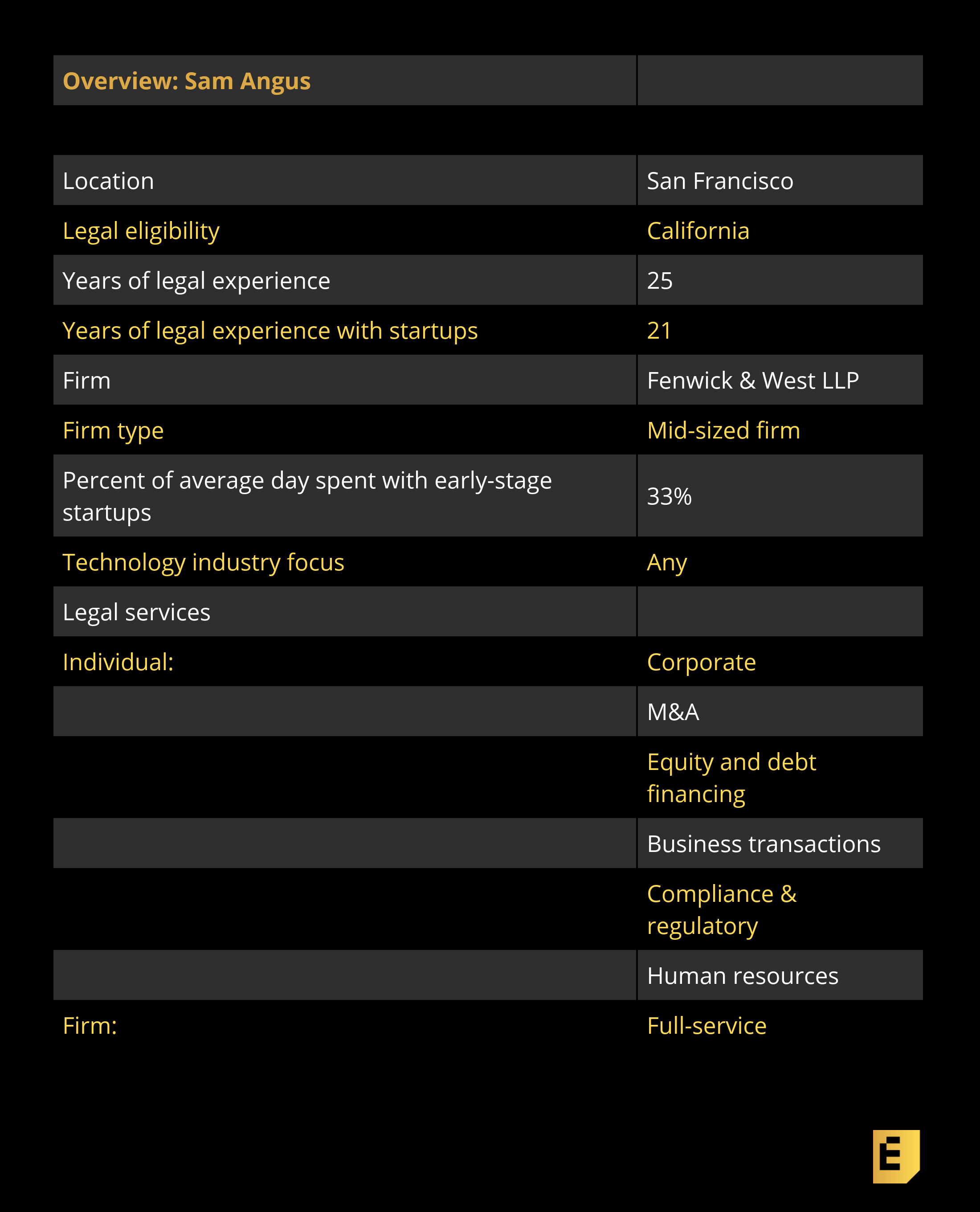

Sam Angus has been a lawyer in Silicon Valley since the 1990s. Today, he represents some of the biggest names in the startup world, from their earliest days through acquisitions and IPOs, and including four acquisitions last year: TSheets, GitHub, Glint and HelloSign.

But his startup experience actually goes back to the 1980s, when he and some friends built a booming calendar publishing business out of their dorm room during college. In the interview below, he tells us about the ups and downs of the tech industry over the decades, how he helps clients through the good times and bad, and how he works within Fenwick & West, one of the leading tech law firms in tech. We also discuss long-term trends, like the shift towards founder-friendly terms in this era versus past decades in the Valley.

On early-stage problems:

“I’ve represented hundreds of early-stage companies. It is not uncommon for companies to have some existing legal issue that needs to be addressed, such as capitalization, documentation and/or employee/IP issues. It is unfortunate, but these issues will frequently — especially with early stage companies — lie dormant and be discovered when the company is contemplating its first financing or a significant transaction, and can take investors or buyers by surprise.

“Sam is one of the most trusted partners that I have ever had and one of the most important people to [the company’s] history.” — A cofounder and CEO of a large unicorn company

“A common mistake is for a company to think that a given issue will not be a concern to an investor or buyers. In my experience, issues that arise on the eve of a financing or other transaction can create risk in the transaction and can be expensive to address quickly. For example, one client I worked with had been operating for years with virtually no documentation and not surprisingly had significant deficiencies in terms of corporate approvals. Very few things are fatal, but the result for this client was a bumpy and more expensive financing process — which required several rounds of explanation to the investors and their counsel.”

On being a startup lawyer:

“What I’ve learned is that the best lawyers for startups bring more than competent legal advice to the relationship – they act like business owners themselves, thinking strategically about the business. The best lawyers have significant experience and a knack for pattern recognition, the combination of which helps identify issues and opportunities in advance of when they become apparent.”

On risk-taking:

“There are some legal risks that early-stage companies will need to take. In my view, my role with earlier stage clients is to position them for success by being practical and focusing them on the issues that are material for a company at their stage of development. Overall, I want to empower clients to push the bounds of what they think is possible, while making wise business and legal decisions that won’t handicap them in the future.

“I would also point out that being able to scale with clients is extremely important. As clients grow, my role evolves to fit their needs – what works for a startup company is different from what a unicorn/growth company will need from their lawyer. With early-stage companies I tend to be more closely involved with the founders and the company’s business, while with later stage companies the relationship becomes more strategic and we tend to support internal legal teams and boards of directors.

Below, you’ll find the rest of the founder reviews, the full interview, and more details like their pricing and fee structures.

This article is part of our ongoing series covering the early-stage startup lawyers who founders love to work with, based on this survey (which we’re keeping open for more recommendations) and our own research. If you’re a founder trying to navigate the early-stage legal landmines, be sure to check out our growing set of in-depth articles, like this checklist of what you need to get done on the corporate side in your first years as a company.

The Interview

Eric Eldon: To begin with, tell me about Fenwick & West. It’s one of the original law firms that started in Silicon Valley and focused on tech companies, and you’ve been there for years through the various cycles.

Eric Eldon: To begin with, tell me about Fenwick & West. It’s one of the original law firms that started in Silicon Valley and focused on tech companies, and you’ve been there for years through the various cycles.

Sam Angus: Launching my career in Silicon Valley has provided me with a unique skillset and perspective that now enables me to thoughtfully advise clients who want to scale quickly, no matter where they are located. Working with fast-growing innovators, like those I’ve served since the tech boom of the 1990s, is in my view different from traditional approaches to practicing law. Providing clients with excellent legal advice is table stakes for any advisor to startups. What I’ve learned is that the best lawyers for startups bring more than competent legal advice to the relationship — they act like business owners themselves, thinking strategically about the business. The best lawyers have significant experience and a knack for pattern recognition, the combination of which helps identify issues and opportunities in advance of when they become apparent. Great startup lawyers also have extensive networks of investors, founders and partners and can leverage these networks to help their clients, address material operational issues, fundraise or complete a strategic transaction. They are efficient/cost-effective and move as quickly as their clients, and, most importantly, provide judgment. This entire skill-set is rare for lawyers, but when it comes in one package it is incredibly valuable to emerging companies. That’s one of the reasons why I love working at Fenwick: this approach to advising startups is simply how we practice.

Eldon: The legal industry is seeing real competition from online services and automation — how are you competing?

Angus: It is true that automation is impacting the practice of law, like other sectors of the economy. Because Fenwick works closely with innovative companies across the globe and sees how technology is changing things, we are among the firms leading the way to embrace this change.

For example, Fenwick has an in-house data and technology innovation team. Our innovation team has developed various automation tools and software products to augment and enhance the services we provide our clients. These include automated forms, client portals where clients can access all the data about their companies (i.e. key corporate documents, cap table, contact information for their Fenwick team, etc.), and use of tools such as Kira, an AI platform that automates aspects of document review in M&A deals, allowing us to close deals at a rapid pace while helping control costs.

Another innovation is our budgeting capability. Fenwick’s budgeting team provides our clients with timely and accurate cost estimates for projects and transactions, such as M&A or IPOs. Leveraging our proprietary deal data about hundreds of similar transactions, we are able to more accurately predict legal costs for our clients.

Eldon: Let’s go back to how you got into working with technology companies and startups.

Angus: In the early 1980s, after a short stint playing professional tennis, I was recruited to play tennis at UC Santa Barbara on a tennis scholarship. While at UCSB, I entered the entrepreneur world, starting UCSB’s first entrepreneur club with two friends in 1984. We also launched our own business, a publishing company that produced and distributed wall calendars.

Our growth was rapid: In our first year we did one calendar title, the next year we expanded to five calendar titles, the year after that 25 calendar titles, the year after that 75 titles, as well as a number of posters and other printed products. As our business grew, we started licensing popular culture content, which was something the calendar industry hadn’t really seen before. We were the first to produce the Michael Jackson calendar and the first Madonna calendar.

Eldon: You did all of this while you were in college?

Angus: Yes, though I ended up taking a break from college in 1987, one quarter shy of completing my degree, to pursue the business full time. By 1989, the company had grown to about 150 US salespeople, ten international distributors, and was doing roughly $50 million annually in gross revenue.

In the end, I ended up selling my interest in the company to the lead investor following resolution of various claims with the investor. Through that experience, I learned firsthand what it’s like to be a founder who had bootstrapped and had scaled the company with complex supply chain … and navigated investor issues.

from TechCrunch https://ift.tt/2UehZUh

via IFTTT

COMMENTS